Blog entry by Bruce McPherson

Image: Dronesense

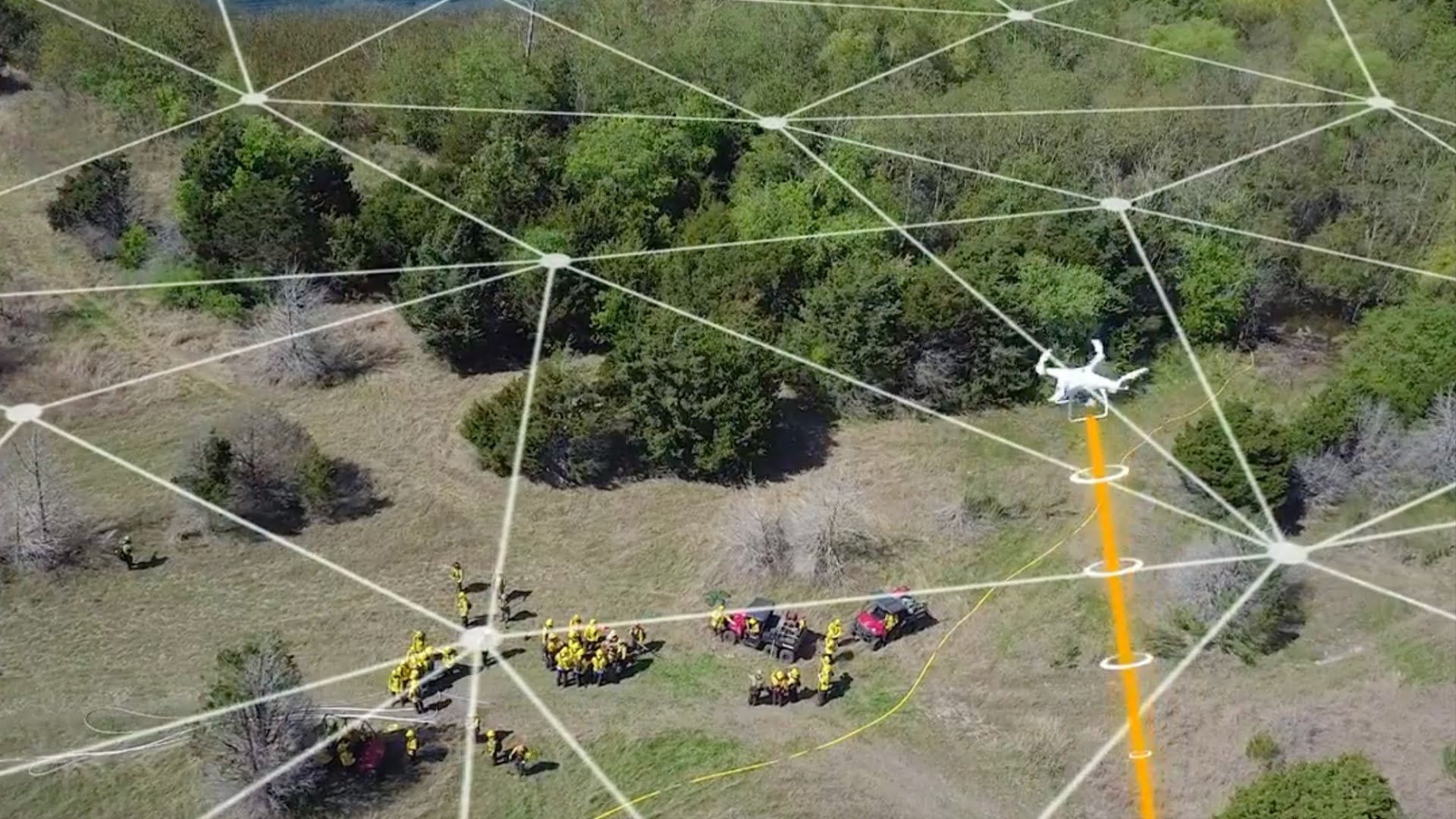

Dronesense, which sells a platform for controlling drones to police, left customer data including flight plans exposed.

Dronesense, a company that sells a platform to government, law enforcement, and private clients for flying drones, exposed a database of customer data, in some cases showing exactly where users programmed their drones to fly.

The exposure not only presented a significant potential risk for the integrity of law enforcement investigations, but also gives new insight into how many police departments, safety services, and businesses are using drones across the United States.

Motherboard obtained some of this data and was able to plot drone flights from a police department onto maps. One showed a drone meticulously scoping out an apartment complex and its car park near Atlanta, Georgia. Another nearby flight marked as "disaster assessment" shows a drone flying over a playground. A third named "Mapping Mission" has nearly two dozen so-called "capture points," likely referring to spots for the drone to photograph, spread across a residential Washington D.C. neighborhood.

"If Dronesense was breached, then it's just another example of law enforcement putting too much faith in new surveillance technologies without fully accounting for the risks," Dave Maass, senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) said in an email. "In addition to potential harms to privacy, insufficient security of law enforcement systems can also undermine the integrity of criminal investigations and even the justice process."

The database is separated by different organizations, such as the Atlanta Police Department, Boise Fire Department, City of Coral Springs, Nassau County Police Department, and even U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The list included over 200 different entries, although some of those appear to be test or administration accounts. No drone camera footage was included, but as well as the flight path data, the data also contained what brand of drone each customer was using for the flight, the pilot's name, email address, and other technical information about the drone.

Dronesense's platform has several components: "Airbase" for storing data, "Pilot" for controlling a drone via an app, and "OpsCenter" to provide visibility into what multiple drones are doing and seeing at once. Cities have used Dronesense's platform for monitoring large events like the Indy 500 race and NFL games.

"Log flights automatically and view detailed playback," the Airbase description reads on Dronesense's website.

Those flight logs are some of the data obtained by Motherboard. As well as the flight marked as "disaster assessment," others are named "Mapping bug test" and "demo 1," suggesting some relate to demos or troubleshooting. In a statement, Dronesense said the data was exposed for just over a month.

Carlos Campos, a spokesperson for the Atlanta Police Department, wrote in an email, "The Atlanta Police Department began using a drone this year to assist us in a number of ways—primarily with providing us a convenient vantage point from which to manage large-scale events such as major sporting events and parades. We contacted DroneSense after your inquiry; the company acknowledged the data exposure and assured us it has taken measures to correct the flaw. We have no reason to believe any law enforcement-sensitive data was compromised as a result of the exposure. Still, the Department values the importance of data security and are discussing the issue further with DroneSense."

Law enforcement and public and private search and rescue organizations have been using drones in the U.S. for several years. Drones have been used to arrest and surveil people and have also been used to locate missing persons and to assist in rescue operations during natural disasters.

When drones were first being incorporated into American airspace, there was much controversy about law enforcement use, with groups like the ACLU and Electronic Privacy Information Center saying that new privacy laws were necessary before their widespread adoption. Several towns and cities put temporary moratoriums on drone use by government actors, but largely the controversy around their use has died down, and police drones have quietly proliferated around the country. According to the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College, at least 599 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. had drones as of 2018. But little research has been done into how those drones are being used, what they are surveilling, and their use in police work.

Do you work for a drone company? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

Noam Rotem, an independent security researcher, discovered the exposed Dronesense data and flagged the issue to both Dronesense and Motherboard. Rotem explained that along with a friend he is scanning the web for leaky databases and came across the Dronesense data.

"Surveillance vendors often provide sales pitches that emphasize everything that can go right when a technology is deployed, but rarely do they address what might happen when the technology fails. This latest incident indicates that law enforcement should exercise more skepticism when acquiring new surveillance systems," Maass added.

When asked a series of questions, Dronesense provided Motherboard with the statement it is sending to its own customers.

"On December 3rd, DroneSense was notified by a security researcher of a potential vulnerability regarding a database located in our cloud-based infrastructure," the statement reads. "Within minutes of this notification, DroneSense identified and corrected a security flaw which had exposed a list of organization names within the DroneSense platform and, for a limited number of organizations, account data. At no time were live video streams or customer uploaded images, videos, documents, or media of any kind exposed by this flaw."